“I hate it when people say we lost her – no you haven’t. She died.”

Audience research: Death, dying and advance care planning

At Compassion in Dying we’ve long been fascinated by how the language we choose to use can influence people’s perception of death and dying. So when we conducted audience research to inform the launch of our new brand, we saw an opportunity to explore the public’s views of the language around death, dying and advance care planning.

We are born, we live and then we all die. We need to normalise it

Looking at our brand through the eyes of the people we support has hugely impacted the language we use. We discovered that some language choices can reinforce unhelpful myths about the end of life and create barriers to accessing services. Whereas other language can help establish the benefits of advance care planning (although we found people prefer the phrase, ‘recording your wishes’) and help us move away from the notion of death being a ‘taboo’. In fact we found that many people want to move on from the language of taboo and shape a new, more open discussion about death and dying.

Methodology

We used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods to gain valuable insight and a robust set of data. This included depth interviews, focus groups, and surveys. We included professionals working around the end of life and in primary care, and two key lay audiences:

- The people we’ve supported

998 people Compassion in Dying had previously supported from our database, no screening criteria applied.

Speaking to people who knew us was important, both to ensure that any changes to our brand and the words we use didn’t alienate those who were already champions of our work. But also to explore how people feel about death, dying and recording their wishes once they’ve done it. - People who might need us in the future

1,018 people aged 30 and over with a nationally representative profile. Additional categories within this group: those with a long-term condition (157) and carers (171).

This was the absolutely critical audience to explore language with, because if we’re going to enable as many people as possible to consider and record their end-of-life wishes, we need to use language that resonates for people who don’t know anything about what we’re doing and why we’re doing it.

What We learnt

‘Good death’ must be explained for it to be motivating

Those who work in palliative care and end-of-life policy have put a lot of thought into what makes a good death. It is at the heart of what the hospice movement aims to achieve, and it consists of different things for different people. What a ‘good death’ looks like for each individual can form the basis of important conversations with them about end-of-life planning. So we wanted to talk about it with the public to see how they reacted to the phrase.

What people told us when we used the phrase ‘good death’, was that it is an oxymoron. But crucially, ‘good death’ IS engaging IF it is followed by an explanation. Like this:

A good life should include a good death. In a place you choose, with the people who matter. Having the care and treatments you want, and not the ones you don’t.

When presented with this context, ‘good death’ was cited by our audiences as motivating language.

People want to move away from euphemism and the language of taboo

“Euphemisms can be frustrating for patients as it feels as though their situation hasn’t been acknowledged. It can be isolating.”

“It should be embraced…. and I think a language needs to be learnt about how to talk about end-of-life care.”

The people we spoke to welcomed a more vocal, pioneering approach to death. They want something that counteracts the silence and the taboo surrounding dying, which they see as negative.

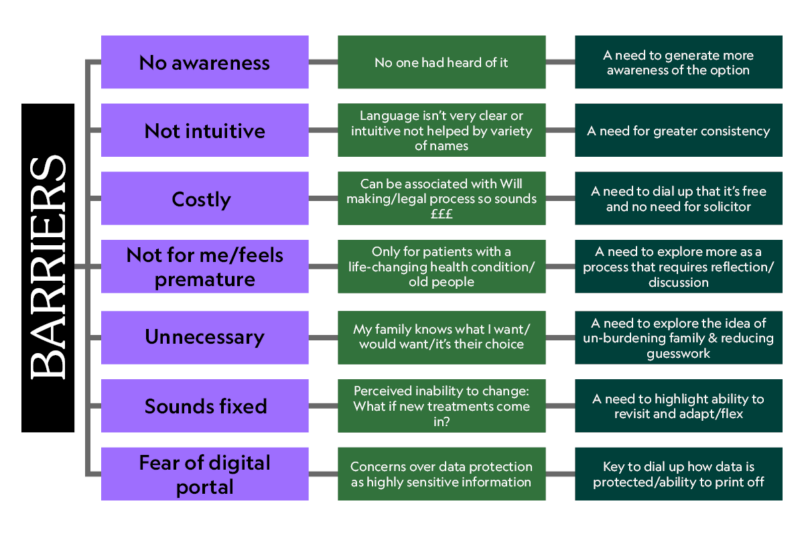

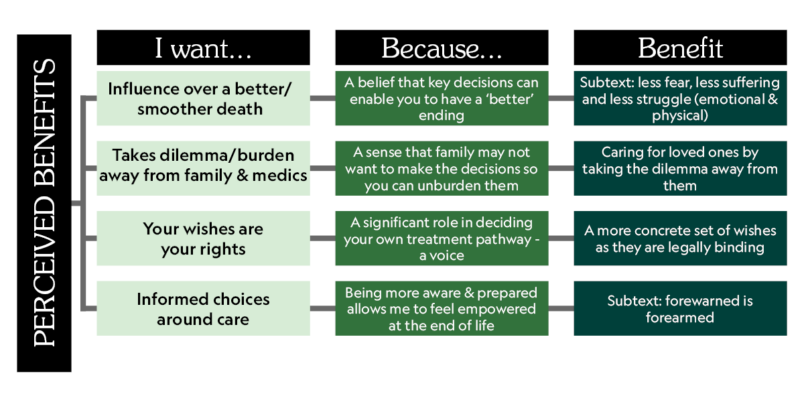

Focusing on the benefits of recording your wishes can overcome the barriers to doing it

Our research with potential service users identified a number of barriers and benefits to someone beginning the process of making an advance decision (living will). In particular, the primary barrier most people identified was that the process sounds fixed, and they might change their mind in future. As with several of the barriers identified below, this reflects an incorrect assumption. We can tackle this, in part, with the language we use. Our new brand will stress that recording your wishes is not fixed, you can change it to suit you. Like this:

You can record and revisit your wishes whenever you want, for free

The most significant of these motivators to complete an advance decision was family. People often expressed it like this:

“Making things easier for family members was my main motivation and I feel it will be for many.”

So we are reflecting this in the copy we use. Like this:

Planning can make things easier for family and loved ones. If you wait until it’s too late, medical professionals may make important decisions without knowing what matters to you

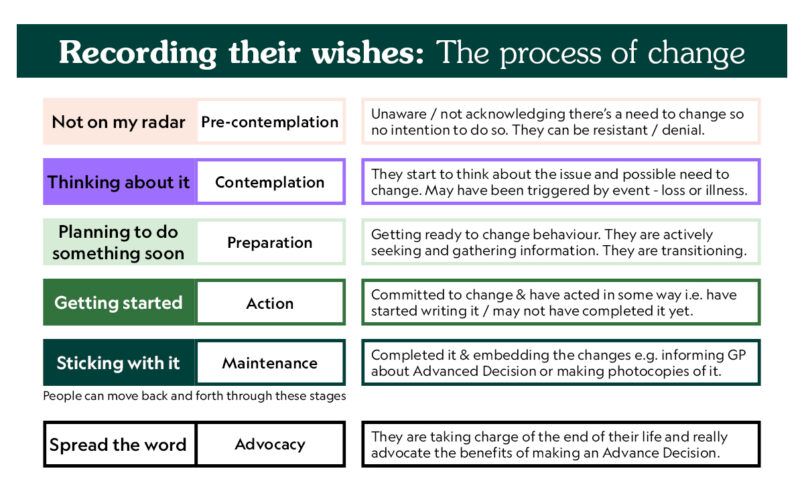

A behaviour change model

When we looked at how people felt and what they went on to do, we realised a person’s journey to recording their wishes can be shown on a behaviour change model.

One finding we were particularly interested in was the advocacy phase – even though we had not asked them to, many people who had recorded their wishes in an advance decision then went on to tell others and advocate for them to do the same. We observed:

- A strong belief: ‘why wouldn’t you have one in place? What have you got to lose?’

- People are selective about who they tell but believe it should be a national conversation, so they don’t have to ‘pussyfoot around it’.

- Often people felt friends are easier to talk to about this than family members.

- There is a firm belief that end-of-life planning must be addressed more openly, and more robust systems put in place to share this information.

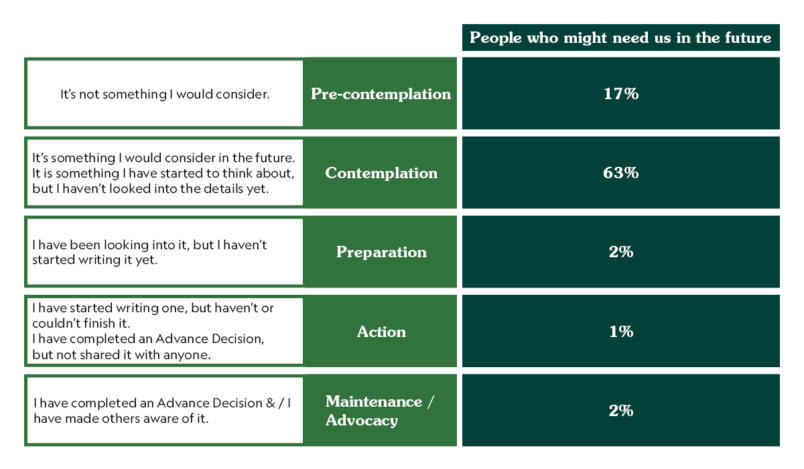

Another finding that has stuck in my mind, is the potential to engage new people in recording their wishes for the end of life. So while the majority haven’t started an advance decision, crucially, most are in the contemplation phase – there’s a clear openness to it in the future.

What next?

This is just the beginning, we have a very full ‘car park’ of ideas that were not fully developed for the launch of our new brand but that we know we want to return to. Some of these I’m most excited about include:

- Developing support for people who want to advocate for planning ahead – if people are already spreading the word how can we help them and develop this?

- Get more people taking action – lots of people would consider recording their wishes but haven’t started because they don’t know how or because of incorrect preconceptions. How can we engage the people who could benefit from recording their wishes and move them through our behaviour change model?

- End the taboo – people are ready to move on from euphemism and taboo. How can we work with others to drive that change?

Credit: My thanks to Abi Markey from Supernova for leading our audience research.

Other blogs in this series

- For your end of life. Your way. The first in a series of blogs to share what we learnt through our journey of creating a clearer brand that speaks up for what people want and need at the end of life.

- No more bodiless hands – our approach to photography – We steer clear of euphemisms when talking about death. Our imagery should be no exception to this.

- Solving whole problems for people – why we’re expanding our service – What people have told us about using advance decisions (living wills) and LPAs, and what we’re doing to help.